Phonemes are the smallest units of sound in spoken language. Phonemic awareness refers to focusing on and manipulating phonemes in spoken words. English has 44 particular phonemes consisting of 24 consonants and 20 vowels.

This article delves into phonemic awareness, its role in reading, and the value of phonemic awareness training.

We specialize in helping children overcome the symptoms of dyslexia and reading difficulties. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

Table of contents:

- Phonological vs. phonemic awareness

- What is phonemic awareness?

- Assessing phonemic awareness skills

- Phonemic awareness and reading

- What is phonemic awareness training?

- Research studies show mixed results

- A cart-before-the-horse approach?

- Conclusion

Phonological vs. phonemic awareness

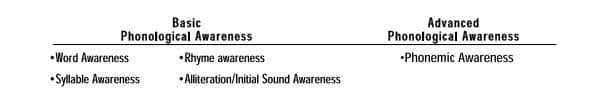

Phonological awareness is an umbrella term. Phonemic awareness is a specific skill under that umbrella term.

Phonological awareness refers to an individual’s awareness of a language’s phonological or sound structure. It is a listening skill that distinguishes speech units, such as rhyme and alliteration, syllables in words, and individual phonemes in syllables. Phonemic awareness is a subset of phonological awareness that focuses on recognizing and manipulating phonemes, the smallest sound units.

In his book Equipped for Reading Success, Kilpatrick (2016) says that phonemic awareness is the most advanced type of phonological awareness and that the other types of phonological awareness provide the foundation for phonemic awareness. These easier phonological skills do not result in skilled reading by themselves. Many children with reading difficulties lack phonemic awareness, but they can demonstrate easier phonological awareness skills.

What is phonemic awareness?

The word phoneme comes from the Greek word phonos, which means “sound.” A phoneme is the smallest unit or sound in oral words. In our alphabet, written letters are designed to represent phonemes used in oral language. For example, the word tap has three phonemes: /t/-/a/-/p/. It also has three letters. Each letter represents one phoneme. However, letters and phonemes are not the same thing. Phonemes are oral, and letters are written. Phonemes are the smallest parts of oral words. Letters are the smallest parts of written words.

Often, phonemes and letters do not match up. For example, there are four letters in bake, but only three phonemes: /b/-/ā/-/k/. The printed word shoe has four letters, but the oral word has only two phonemes (i.e., two sounds). The sh represents one sound, and the vowels team oe makes one sound. Thus, four letters represent two phonemes. So, bake and shoe do not have a one-to-one match between letters and phonemes.

Assessing phonemic awareness skills

The following tasks are commonly used to assess children’s phonemic awareness or to improve their phonemic awareness through instruction and practice (Tønnessen & Uppstad, 2015):

- Phoneme isolation requires recognizing individual sounds in words, for example, ‘Tell me the first sound in paste.’ (/p/)

. - Phoneme identity requires recognizing the common sound in different words. For example, ‘Tell me the sound that is the same in bike, boy, and bell.’ (/b/)

. - Phoneme categorization requires recognizing the word with the odd sound in a sequence of three or four words, for example, ‘Which word does not belong? bus, bun, rug.’ (rug)

. - Phoneme blending requires listening to a sequence of separately spoken sounds and combining them to form a recognizable word. For example, ‘What word is /s/-/k/-/ü/-/l/?’ (school)

. - Phoneme segmentation requires breaking a word into its sounds by tapping out or counting the sounds or by pronouncing and positioning a marker for each sound. For example, ‘How many phonemes are there in ship?’ (three: /sh/-/i/-/p/)

. - Phoneme deletion requires recognizing what word remains when a specified phoneme is removed. For example, ‘What is smile without the /s/?’ (mile)

In other words, ‘phonemic awareness’ is made into a very broad concept. The demands placed on the ability to concentrate and to think abstractly are great.

Phonemic awareness and reading

The ability to segment and blend phonemes is considered especially critical for developing reading skills, including decoding and fluency, and even that it predicts reading ability (Taylor, 1998; Moustafa, 2001). Decoding is the ability to break a word up into its individual letters or groups of letters, identify the corresponding sounds, and then blend the sounds together to read the word. Fluency is, quite simply, the ability to read quickly and accurately.

Marilyn Jager Adams concluded that phonemic awareness is the “most important core and causal factor separating normal and disabled readers” (Adams, 1990, pp. 304-5). Kilpatrick (2016) states that phonological awareness training prevents and corrects reading difficulties (p. 13).

The phonological deficit theory became the most prevalent cognitive-level explanation for the cause of reading difficulties and dyslexia. It has been widely researched in the U.K. and the U.S., resulting in a remarkable consensus concerning the causal role of phonological skills in young children’s reading progress. Children with good phonological skills, or good “phonological awareness,” become good readers and spellers. Conversely, children with poor phonological skills progress more poorly. In particular, those who have a specific phonological deficit are likely to be classified as dyslexic by the time they are nine or ten years old (Goswami, 1999).

What is phonemic awareness training?

Phonemic awareness training teaches children to focus on and manipulate phonemes in spoken syllables and words. “Basic” skills include phonemic segmentation (e.g., ‘Tell me each sound you hear in cat’) or phoneme blending (e.g., ‘What word do these sounds make: /k/-/a/-/t/‘).

Some scholars advocate advanced phonemic awareness, which includes phoneme deletion (e.g., ‘Say cat without /k/‘) and phoneme replacement (e.g., ‘Say cat. Now change the /k/ to /p/‘), including medial sounds or sounds in blends (e.g., ‘Say bat. Now change the /a/ to /i/‘; or, ‘say stop. Now change /t/ to /l/‘).

These perspectives have been disseminated as evidence-based and consistent with the “science of reading.” They might be and are used by states in the U.S. for crafting policies on reading instruction and evaluating reading programs (Clemens et al., 2021).

Research studies show mixed results

Studies have investigated the effects of phonemic awareness training on reading outcomes and have demonstrated mixed results.

Reading and Van Deuren (2010) assessed the literacy skills of 92 first-grade children; one group received instruction in phonemic awareness in kindergarten, while one group did not. Both groups received phonemic awareness instruction during first grade.

At the beginning of first grade, the group with early phonemic awareness training scored higher on phoneme segmentation and had fewer children identified with reading difficulties. By the middle of first grade, the literacy skills of children without early training were comparable to those of children with such training in kindergarten.

Results suggest that learning phonemic awareness skills during first grade supports grade-level reading; learning phonemic awareness skills can occur within a short period, and learning these skills beyond a sufficient level does not necessarily result in improved oral reading fluency.

Weiner (1994) investigated the effect of phonemic awareness training on the phonemic awareness and reading ability of 79 low- and middle-achieving first-grade readers.

Random assignment was made to one control group and three experimental: phonemic skill training only (“skill and drill”), phonemic skill training plus decoding (“semi-conceptual”), and phonemic skill training plus decoding and reading (“conceptual”). Outcome measures included segmentation, deletion, deletion, and substitution tests, as well as standardized and informal reading tests.

Results indicated no significant differences among the experimental and control groups on measures of phonemic awareness (segmentation excepted) or reading. Findings also revealed that training that provided subjects with a conceptual connection between phonemic skills and reading was generally ineffective for low readers. These results suggest that phonemic awareness training for low- and middle-achieving beginning readers may not be unequivocally beneficial.

The recent positions about advanced phonemic awareness, especially, have sparked debate. Scholars have argued that advanced phonemic awareness training is inconsistent with reading research, and related recommendations lack evidence (Brown et al., 2021; Shanahan, 2021).

A cart-before-the-horse approach?

Moustafa points out that the correlation between phonemic awareness and reading does not establish causation. For example, a high correlation exists between being sick and being in a hospital. However, the hospital did not cause the illness. “In statistics, the word ‘predicts’ means nothing more than that there is a high correlation between two phenomena” (Moustafa, 2001, p. 248).

“Research does not support phonemic awareness training,” continues Moustafa:

Bus & van Ijzendoorn (1999) found that phonemic awareness in kindergarten accounts for 0.6 % of the total variance in reading achievement in the later primary years. Troia (1999) reviewed 39 phonemic awareness training studies and found no evidence to support phonemic awareness training in classroom instruction. Krashen (1990a, 1999b) conducted similar reviews and had similar findings. Taylor (1998) points out that phonemic awareness research is based on the false assumption that children’s early cognitive functions work from abstract exercises to meaningful activity, rather than vice-versa, as in other learning.

Tønnessen and Uppstad (2015) point out that there are very good readers who do not perform particularly well in the six areas mentioned above (phoneme isolation, identity, categorization, blending, segmentation, and deletion). Thus, the extent to which phonemic awareness is necessary for reading can be questioned.

Some findings indicate that phoneme awareness may develop as a consequence of exposure to reading and writing. Research showing that adult illiterates and readers of a non-alphabetic script lack awareness of phonemes is especially persuasive.

Phonemic awareness training is a cart-before-the-horse approach to teaching reading, Moustafa concludes.

Conclusion

Some level of phonemic processing is undoubtedly important for beginning reading instruction. O’Connor (2011) concluded that the ability to segment and blend three to four sounds in short words provides a sufficient foundation for word-reading and spelling instruction.

Edublox strongly supports the conclusions of the National Reading Panel (2000) and the What Works Clearinghouse (Foorman et al., 2016) that young students benefit from phonemic awareness instruction to learn to read and spell words. However, evidence does not exist that continued instruction in increasingly sophisticated phonemic skills benefits reading outcomes and that attaining proficiency with complex phonemic manipulation is necessary for introducing more advanced word reading.

Clemens et al. (2021) state:

Although promoted as evidence-based, proficiency in so-called advanced phonemic skills is not more strongly related to reading or more discriminative of difficulties than other phoneme-level skills, not necessary for skilled reading, and is more likely a product of learning to read and spell than a cause. Additionally, reading outcomes are stronger when phonemic awareness is taught with print; there is no evidence that advanced phonemic awareness training benefits reading instruction or intervention, and prominent theories of reading development do not align with the claims.

Recent developments in dyslexia research have led many scholars to conclude that previous theories based on a single deficit, such as the phonological deficit theory, are inadequate. Current thinking sees phonemic awareness as one of multiple deficits that are likely to interact to cause reading disability (Peterson & Pennington, 2012; Pennington, 2006).

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and other learning disabilities. Our students are in the United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

Authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational and reading specialist with 30+ years of experience in the learning disabilities field.

References:

Adams, M. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Brown, K. J., Patrick, K. C., Fields, M. K., & Craig, G. T. (2021). Phonological awareness materials in Utah kindergartens: A case study in the science of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56: S249-S272.

Clemens, N., Solari, E., Kearns, D. M., Fien, H., Nelson, N. J., Stelega, M., … & Hoeft, F. (2021). They say you can do phonemic awareness instruction “in the dark”, but should you? A critical evaluation of the trend toward advanced phonemic awareness training. PsyArXiv Preprints

Foorman, B., Beyler, N., Borradaile, K., Coyne, M., Denton, C. A., Dimino, J., … & Wissel, S. (2016). Foundational skills to support reading for understanding in kindergarten through 3rd grade. Educator’s Practice Guide. What Works Clearinghouse.

Goswami, U. (1999). Integrating orthographic and phonological knowledge as reading develops: Onsets, rimes, and analogies in children’s reading. In R.M. Klein & P. McMullen (Eds.). Converging methods for understanding reading and dyslexia (pp. 57-75). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Kilpatrick, D. A. (2016). Equipped for reading success. Syracuse: Casey & Kirsch Publishers.

Moustafa, M. (2001). Contemporary reading instruction. In T. Loveless (Ed.). The great curriculum debate: How should we teach reading and math? (pp. 247-67). Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

National Reading Panel (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

O’Connor, R. E. (2011). Phoneme awareness and the alphabetic principle. In R. E. O’Connor & P. Vadasy (Eds.), Handbook of reading interventions (pp. 9-26). Guilford Press.

Pennington, B. F. (2006). From single to multiple deficit models of developmental disorders. Cognition, 101(2): 385-413.

Peterson, R. L., & Pennington, B. F. (2012). Developmental dyslexia. The Lancet, 379: 1997–2007.

Reading, S., & Van Deuren, D. (2007). Phonemic awareness: When and how much to teach? Reading Research and Instruction, 46(3): 267–285.

Shanahan, T. (2021). RIP to advanced phonemic awareness. https://tinyurl.com/ycxf3dsn.

Taylor, D. (1998). Beginning to read and the spin doctors of science. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Tønnessen, F. E., & Uppstad, P. H. (2015). Can we read letters? Reflections on fundamental issues in reading and dyslexia research. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Weiner, S. (1994). Effects of phonemic awareness training on low- and middle-achieving first graders’ phonemic awareness and reading ability. Journal of Reading Behavior, 26(3): 277–300.