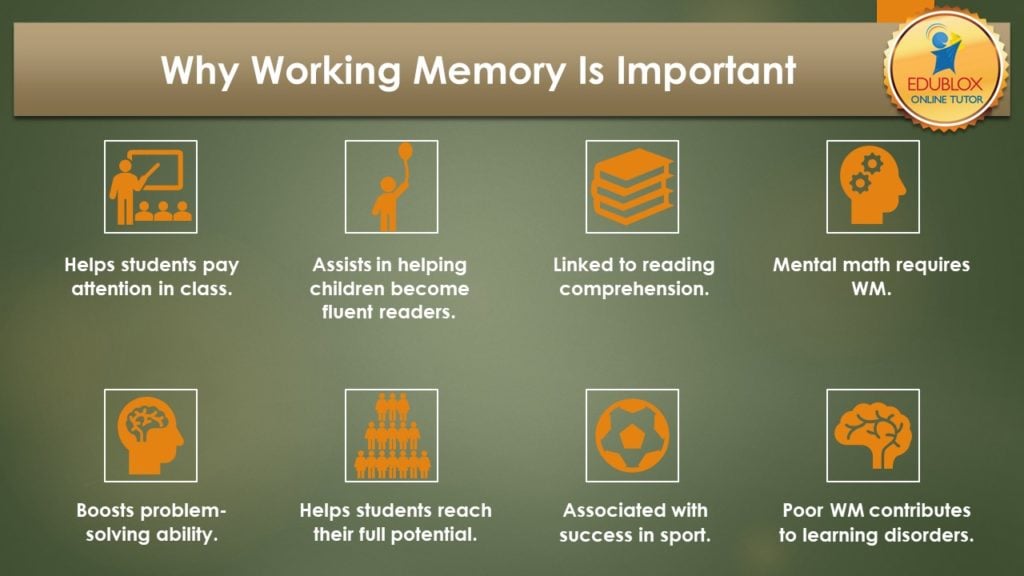

Working memory is critical to learning. How good this is in someone will ease or impair learning. Here are eight reasons why working memory is important.

What is working memory?

Working memory is the mental ability to store and manipulate information temporarily. Its functioning is distinct from the vast storage capacity of long-term memory and is crucial for optimal learning and development.

You need this kind of memory to retain ideas and thoughts as you work on problems. In writing a letter, for example, you must be able to keep the last sentence in mind as you compose the next. Likewise, to solve an arithmetic problem like (3 X 3) + (4 X 2) in your head, you need to keep the intermediate results in mind (i.e., 3 X 3 = 9) to be able to solve the entire problem.

Dr. Tracy Alloway from Durham University’s School of Education explains, “Working memory is a bit like a mental jotting pad, and how good this is in someone will either ease their path to learning or seriously prevent them from learning.”

The distinction between short-term and working memory is an ongoing debate, and the terms are often used interchangeably. Some scholars claim that some manipulation of remembered information is needed to qualify the task as one of working memory. For example, repeating digits in the same order they were presented would thus be a short-term memory task, while repeating them backward would be a working memory task.

Another viewpoint is that of Nelson Cowan, who says short-term memory refers to the passive storage of information when rehearsal is prevented, with a storage capacity of around four items. However, when rehearsal is allowed and controlled attention is involved, it is a working memory task, and the capacity is closer to seven items.

Working memory is key to learning. Here are eight ways children use working memory to learn.

1. Working memory helps students pay attention

Students’ ability to pay attention during class and schoolwork requires them to process and retain information via working memory.

Students with strong working memory are likely to do well in maintaining focus and attention in various academic settings. They can more readily be left to work independently because they’re capable of processing and remembering instructions and task goals.

One of the most consistent findings in research studies is that students with ADHD have a poor working memory, particularly when they have to remember visual information, such as graphs or images. Students with ADHD are four times more likely to have working memory problems compared to peers without attention problems.

2. Working memory assists in helping children become fluent readers

Working memory is responsible for many of the skills children use to learn to read. Auditory working memory helps kids hold on to the sounds letters make long enough to sound out new words. In contrast, visual working memory helps kids remember what those words look like so they can recognize them throughout the rest of a sentence.

When working effectively, these skills keep kids from having to sound out every word they see, enabling them to read with less hesitation and become fluent readers. Unfortunately, learning to read isn’t as smooth for kids with weak working memory skills.

3. Working memory is linked to reading comprehension

Research has shown a distinct link between working memory and reading comprehension.

When students with weak working memory skills read a paragraph, they may forget what was at the beginning of the paragraph by the time they get to the end. As a result, these students will look like they have difficulty with reading comprehension. They do, but the comprehension problem is due to a failure of the memory system rather than the language system.

4. Mental math requires working memory

Students with poor working memory often forget what they are doing while doing it. For example, they may understand the three-step direction they were just given but forget the second and third steps while carrying out the first step.

Doing math in “your head” — or mental math — requires significant working memory. Children need to store the information they have heard, be able to recall and retrieve those facts, and then process the information correctly to apply it.

5. Working memory boosts problem-solving

According to University of Michigan research, improving working memory can boost scores in general problem-solving ability and improve fluid intelligence. Fluid intelligence is the ability to solve new problems, use logic in new situations, and identify patterns. In contrast, crystallized intelligence is the ability to use learned knowledge and experience.

6. Working memory helps students reach their full potential

Researchers from Durham University surveyed over three thousand children and concluded that children who underachieve at school might have poor working memory rather than low intelligence. They found that ten percent of schoolchildren across all age ranges suffer from poor working memory, seriously affecting their learning.

The researchers found that poor working memory is rarely identified by teachers, who often describe children with this problem as inattentive or having lower levels of intelligence. Without appropriate intervention, poor working memory in children can affect long-term academic success into adulthood and prevent children from achieving their potential.

7. Working memory is associated with success in sports

A study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden showed a strong link between executive functions, such as working memory, and achievement in sports. The study showed that working memory and other cognitive functions in children and young people could be associated with their success on the soccer pitch.

Executive functions are special control functions in the brain that allow us to adapt to an environment in a perpetual state of change. They include creative thinking to switch strategies quickly, find new, effective solutions and repress erroneous impulses. These functions depend on the brain’s frontal lobes, which continue to develop until age 25.

Strong results for several executive functions were found to be associated with success on the pitch, even after controlling for other factors that could conceivably affect performance. The clearest link was seen for simpler forms of executive function, such as working memory, which develops relatively early in life.

8. Poor working memory contributes to learning disorders

Working memory deficits have been documented for different learning disorders, and improving working memory is imperative in overcoming such disorders.

Weiss and colleagues tested 52 musicians, of which 24 have dyslexia and 28 who do not have dyslexia, and compared the performance of the two groups in various auditory tests. On most auditory processing tests, the dyslexic musicians scored as well as their nondyslexic counterparts and better than the general population. However, they performed much worse on tests of auditory working memory, including memory for rhythm, melody, and speech sounds. Moreover, these abilities were intercorrelated and highly correlated with their reading accuracy, which means that the dyslexic musicians with the poorest working memory tended to have the lowest reading accuracy. Conversely, those with better working memory tended to be more accurate.

Improving working memory is imperative to overcoming learning disorders. Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and other learning disabilities. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

.

Key takeaways

Authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational specialist with 30+ years’ experience in the learning disabilities field.

.

References and sources:

Cowan, N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24.

Maehler, C., & Schuchardt, K. (2016). Working memory in children with specific learning disorders and/or attention deficits. Learning and Individual Differences, 49, 341–347.

Vestberg, T., Reinebo, G., Maurex, L., Ingvar, M., & Petrovic, P. (2017). Core executive functions are associated with success in young elite players. PloS one, 12(2), e0170845.

Weiss, A. H, Granot, R. Y., & Ahissar, M. (2014). The enigma of dyslexic musicians. Neuropsychologia, 54, 28-40.