The history of dyslexia starts in 1877, 147 years ago. A German neurologist, Adolph Kussmaul, may be considered the first person whose work drew public attention to reading difficulties. Kussmaul named it word blindness and called for studying reading problems as a specific learning difficulty. The term spread fast among educators and medical practitioners.

Table of contents:

- Berlin, Kerr and Morgan

- Hinshelwood and Orton

- Dyslexia in the 1960s

- Samuel A. Kirk

- Education for All Handicapped Children Act

Berlin, Kerr and Morgan

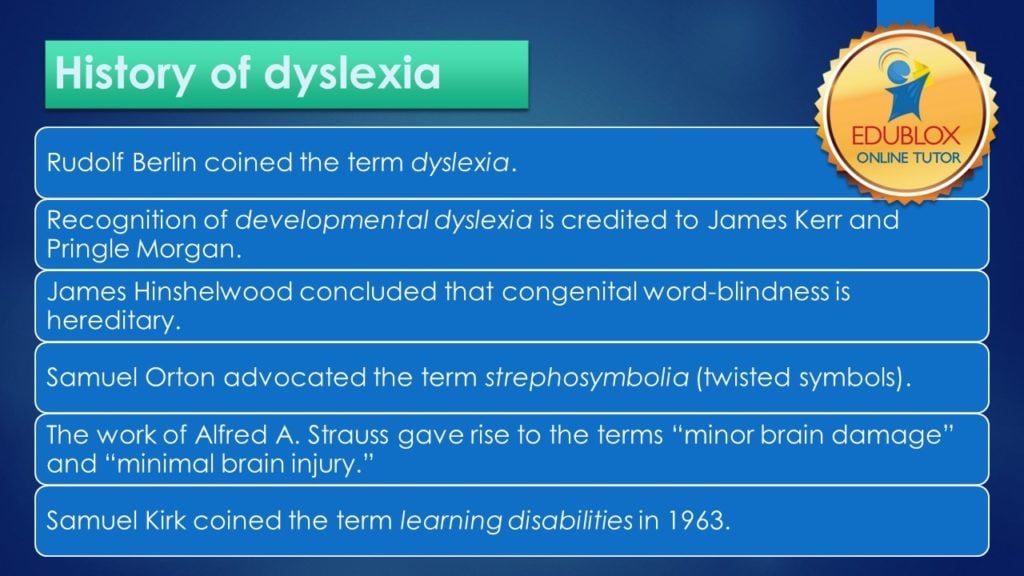

Rudolf Berlin, an ophthalmologist in Germany, introduced the term dyslexia in 1884, bringing it in line with other common diagnoses of the time: alexia and paralexia (Kirby, 2020). He coined it from the Greek words dys meaning ill or bad, and lexis, meaning word, and detailed his observations of six patients with brain lesions who had lost the ability to read, yet their speech was fully intact. Today we refer to this type of dyslexia as acquired dyslexia.

Developmental dyslexia, however, refers to the failure to learn to read competently. Pringle Morgan and James Kerr get credit for recognizing developmental dyslexia. In an article in The Lancet titled “A case of congenital word blindness,” Morgan (1896) identified a 14-year-old boy called Percy, who, despite adequate intelligence, could not even write his name correctly.

Morgan described the boy as “bright and of average intelligence in conversation. His eyes are normal, there is no hemianopsia, and his eyesight is good. Nevertheless, the schoolmaster who has taught him for some years says that he would be the smartest lad in the school if the instruction were entirely oral” (p. 1378).

Hinshelwood and Orton

James Hinshelwood, a British opthalmologist, and the American neurologist Samuel Orton took up the concept. Expanding on the work of Berlin and Morgan, Hinshelwood attempted to identify both acquired and developmental dyslexia and concluded that while acquired word blindness is a neurological condition owing to brain injury, congenital word blindness is hereditary but remediable and more common in boys. Hinshelwood attributed congenital word blindness to a lesion in the left angular gyrus, which impaired the ability to store and remember visual memories of letters and words.

On the other hand, Orton advocated the term strephosymbolia (twisted symbols) to indicate that the problem was not one of word blindness per se but that visual impressions were ‘distorted’ in the perceptual processing of letters and words.

In 1919, Orton was hired as the founding director of the State Psychopathic Hospital in Iowa City, Iowa, and chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Iowa College of Medicine. In 1925, he set up a 2-week mobile clinic in Greene County, Iowa, to evaluate students referred by teachers because they “were retarded or failing in their school work.” Orton found that 14 students who were referred primarily because they had great difficulty learning to read had near-average, average, or above-average IQ scores.

Hinshelwood had also noted that many of his cases of congenital word blindness were intelligent. With the advent of IQ tests, Orton was able to lend a certain degree of objectivity to this notion. Whereas Hinshelwood had bristled at the idea that one per thousand students in elementary schools might have “word blindness,” Orton offered that “somewhat over 10 percent of the total school population” had reading disabilities (Orton 1925 & 1939, as cited by Hallahan & Mercer, 2002).

Working from 1925 onwards, Orton studied over 1,000 children. His observations persuaded him that children with dyslexia were especially prone to left-right confusion and reversals, such as mistaking b for d or was for saw. Orton concluded that dyslexia was due to a failure to establish a left-right sense, which was, in turn, caused by incomplete cerebral dominance. He developed several teaching strategies with his assistant, Anna Gillingham, some of which are still in use.

Orton’s work inspired many, including the neurologist Norman Geschwind, and led to the foundation of the Orton Dyslexia Society, now the International Dyslexia Association. As a result of Orton’s research, dyslexia passed from medical to educational ownership. This led to it being ‘treated’ by educational development rather than medical intervention (Macdonald, 2010).

Dyslexia in the 1960s

At the beginning of the 20th century, only a small number of children were diagnosed with congenital word-blindness or dyslexia. Because their features were distinct from the recognized handicap categories, they were deprived of formal special education services. This situation changed in the 1960s, following research on brain-injured adolescents by two Jewish scholars, Alfred A. Strauss and Heinz Werner.

Amid the developing holocaust, Alfred A. Strauss and Heinz Werner began making their way to the United States via separate routes. They came together in 1937 at the Wayne County Training in Northville and started a collaboration that laid the cornerstone for what today is known as the field of learning disabilities.

Strauss and Werner observed that the intellectually disabled adolescents in their care manifested the same perceptual, mood, and learning disorders that Kurt Goldstein had found in head-injured soldiers. Following World War 1, Goldstein studied a large number of brain-injured soldiers intensively and for long periods. These studies led to entirely novel conceptions of problems such as aphasia, agnosia, and tonus disturbances, and systematic descriptions of behavioral changes wrought by brain injury. Goldstein also devised rehabilitation programs aimed at returning brain-injured soldiers to some level of productivity.

Based on their symptoms, Strauss and Werner divided their students into two groups: the endogenous type comprised students with a family history of mental deficiency; the exogenous type had no family history of mental deficiency. According to Strauss and his partner, their intellectual disability was caused by brain injury — before, during, or after birth.

In comparing endogenous and exogenous adolescents on perceptual and cognitive tasks, they found the endogenous group to be more successful than the brain-injured adolescents regarding these abilities. In addition, the endogenous group had no behavioral problems, while the brain-injured group engaged in — what they described as — disturbed, unrestrained and volatile behavior (Franklin, 1987).

Kavale and Forness (1985) reanalyzed Strauss and Werner’s original studies on brain-injured children. They concluded that the performance differences reported between the two groups of children — the endogenous and exogenous — were too small to justify Strauss and Werner’s distinction.

Birth of a ‘minimal brain dysfunction’

Strauss and coworkers Kephart and Lehtinen extended Goldstein’s study of head-injured adults and Strauss and Werner’s study of brain-injured adolescents to children. These studies included “children with known brain damage, such as cerebral palsy,” but also “samples of children who evidenced learning and behavior problems but did not show clinical signs of brain damage” (Kaufman, 2008, p. 3).

Strauss and his new coworkers argued that the kind of perceptual-motor and cognitive problems and behavior problems that Strauss and Werner had found among the exogenous group were not only to be found in mentally defective children. These problems were also found in children of normal intelligence. They concluded that children of normal intelligence, who exhibited these learning and behavior problems, were also brain damaged, giving rise to the terms “minor brain damage” and “minimal brain injury” (Franklin, 1987).

While this line of reasoning comprises an invalid argument — if A then B; B; therefore A — this moved the field forward dramatically. The term “brain damage” was, however, mitigated to a less harmful one, namely minimal brain dysfunction, and dyslexia, together with at least one hundred childhood problems such as strabismus and “sleeping abnormally light or deep,” were included in this all-compassing term (Clements, 1966) — a term no longer in use.

Lehtinen

Lehtinen’s early work suggested that remediation of the perceptual disorders was feasible and was followed by a plethora of visual-perceptual-motor training programs to rectify children’s minimal brain dysfunctions. Names like Frostig, Ayres, Getman, Kephart, and Barsch, associated with different methodologies on the same theme, dominated the 1960s.

However, subsequent systematic reviews of 81 research studies, encompassing more than 500 different statistical comparisons, concluded that “none of the treatments was particularly effective in stimulating cognitive, linguistic, academic, or school readiness abilities and that there was a serious question as to whether the training activities even have value for enhancing visual perception and/or motor skills in children indicated” (Hammill & Bartel, 1978, as cited by Kaufman, 2008, p. 3)..

Samuel A. Kirk

In 1963 Samuel A. Kirk coined the term learning disabilities (LD) to describe children with disorders in the development of language, speech, reading, and associated communication skills. He introduced it to a large group of parents in Chicago, Illinois. They enthusiastically accepted the term and, shortly after that, established the Association for Children with Learning Disabilities.

In a rush to generate public awareness of the condition of dyslexia, advocacy groups, with the cooperation of a compliant media, have perpetuated the belief that a host of famous individuals such as Albert Einstein, Leonardo da Vinci, Thomas Edison, Walt Disney, and Hans Christian Andersen had dyslexia.

The folk myth — the “affliction of the geniuses” — continues to be spread even though the fact that knowledge of the definition of dyslexia and the reading of any standard biographies would immediately reveal the inaccuracy of many such claims (Stanovich, 1989). For example, as Coles (1987) points out, Einstein’s reading of Kant and Darwin at age thirteen hardly represents individuals currently labeled dyslexic. Likewise, a systematic study of Hans Christian Andersen’s diaries, letters, and poems from age 20 to 70 concluded that “in all probability, the notion that Andersen had dyslexia is a myth” (Kihl et al., 2000).

Nevertheless, with the backing of parent movements and advocacy groups, the LD enterprise became “an enormous machine — indeed a factory — with attending cottage industries, fueled by legal, socio-political, educational, and entrepreneurial energy” (Moats & Lyon, 1993, p. 283).

Education for All Handicapped Children Act

With the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA) in 1975, learning disabilities were officially recognized by the United States Department of Education. Public schools were required to identify students with learning disabilities and provide them with special education services. The federal government mandated the need for a substantial discrepancy between a child’s achievement level and his or her potential for achievement, leaving it for each state to decide how to determine whether a student had a severe discrepancy.

However, it is difficult to find a discrepancy because students are still too young to obtain meaningful and reliable reading and math scores until third and fourth grade. This situation has resulted in the IQ-achievement approach being labeled a “wait-to-fail” model (Hallahan, Kauffman, & Pullen, 2015). In its place, policymakers have proposed what is referred to as a response to intervention (RTI) approach.

Variations exist, but RTI usually consists of three tiers of instruction. Tier 1 is typical instruction (with the important provision that it be evidence-based) delivered in the general education classroom. Students not doing well in Tier 1 are provided more intensive instruction in small groups several times a week (Tier 2). Those still struggling following Tier 2 interventions are referred for special education evaluation, with special education being Tier 3.

Terminology

The term word blindness is now obsolete. This is also true of such less known and infrequently used terms as word amblyopia, thypholexia, amnesia visualis verbalis, analfabetia partialis, bradylexia, script-blindness, psychic blindness, symbolia confusion, primary reading retardation, and developmental reading backwardness. Even the term coined by Orton, strephosymbolia, never caught on, despite the popularity of his theory (Gjessing & Karlsen, 1989).

Most of these terms have now been discarded in favor of the terms dyslexia, reading disability, and learning disability, with learning disabilities (LD) as the umbrella term for various learning difficulties, including dyslexia. Dyslexia is categorized as a “specific learning disorder” in the DSM-5, published in 2013 (American Psychiatric Association).

.

.

History of dyslexia – key takeaways

Edublox offers live online tutoring to students with dyslexia. Our students are in the United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

.

References:

Clements, S. D. (1966). Minimal brain dysfunction in children; terminology and identification. Phase one of a three-phase project. U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Retrieved August 16, 2024, from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED022289.pdf

Coles, G. S. (1987). The learning mystique. New York: Pantheon Books.

Franklin, B. M. (1987). From brain injury to learning disability: Alfred Strauss, Heinz Werner and the historical development of the learning disabilities field. In B. M. Franklin (Ed.), Learning disability: Dissenting essays (pp.29-46). Philadelphia: The Falmer Press.

Gjessing, H-J., & Karlsen, B. (1989). A longitudinal study of dyslexia: Bergen’s multivariate study of children’s learning disabilities. New York: Springer-Verlag New York.

Hallahan, D. P., Kauffman, J. M., & Pullen, P. C. (2015). Exceptional learners: Introduction to special education (13th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Kaufman, A.S. (2008). Neuropsychology and specific learning disabilities: Lessons from the past as a guide to present controversies and future clinical practice. In E. Fletcher-Janzen & C.R. Reynolds (Eds.) Neuropsychological perspectives on learning disabilities in the era of RTI: Recommendations for diagnosis and intervention (pp. 1-13). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Kavale, K. A., & Forness, S. R. (1985). The science of learning disabilities. San Diego: College Hill Press.

Kihl, P., Gregersen, K., & Sterum, N. (2000). Hans Christian Andersen’s spelling and syntax. Allegations of specific dyslexia are unfounded. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 33(6): 506-519.

Kirby, P. (2020). Dyslexia debated, then and now: A historical perspective on the dyslexia debate. Oxford Review of Education, 46(4): 472-486.

Macdonald, S. J. (2010). Towards a sociology of dyslexia: Exploring links between dyslexia, disability and social class. VDM Verlag Dr. Müller.

Moats, L. C., & Lyon, G. R. (1993). Learning disabilities in the United States: Advocacy, science, and the future of the field. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 26: 282-94.

Morgan, W. P. (1896). A case of congenital word blindness. The Lancet, 2(1871): 1378.

Stanovich, K. E. (1989). Learning disabilities in broader context. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 22(5): 287-91.