Discover a comprehensive, research-informed approach to dyslexia treatment that goes beyond phonics. This four-pillar model integrates structured instruction, cognitive training, targeted brain development, and foundational learning principles to help children overcome reading challenges.

.

Table of contents:

- Introduction

- Orton-Gillingham as a treatment for dyslexia

- Dyslexia treatment and cognitive training

- Dyslexia treatment targeting two brain regions

- Learning principles in dyslexia treatment

- The bottom line

Introduction

Why do so many bright, curious children struggle to read? For over a century, this question has puzzled parents, teachers, and scientists alike.

“Word blindness” was the first term used to describe a reading disability. Today, we call it dyslexia — a difficulty with words. Like all words beginning with dys, it points to a problem or deficiency, while lexia relates to words and language. Dyslexia, therefore, means “difficulty with reading and writing words.”

Children with dyslexia often read haltingly, spell poorly, and may struggle with numbers as well — sometimes despite years of tutoring and effort. The mismatch between their intelligence and their reading ability can be heartbreaking.

For decades, researchers have searched for the cause and the cure. Theories have come and gone, yet dyslexia is still widely viewed as a lifelong condition (Novembli & Azizah, 2019; Knowles, 2017). Perhaps the solution does not lie in a single method, but in combining several complementary approaches.

Edublox’s dyslexia treatment program is built on four interlocking pillars:

- The Orton–Gillingham approach,

- Cognitive training,

- The development of two crucial brain regions for reading, and

- Proven learning principles that make reading instruction effective and lasting.

.

Together, these pillars form a comprehensive framework — addressing the how, the where, and the why of reading difficulty — and offering new hope to children with dyslexia.

Orton-Gillingham as a treatment for dyslexia

Edublox’s dyslexia treatment program aligns with the respected Orton–Gillingham (OG) approach, developed by educator Anna Gillingham and grounded in the neurological research of Dr. Samuel Orton.

Orton, a pioneering American neurologist, studied over a thousand children and noticed a recurring pattern: those with dyslexia often struggled with left–right confusion and reversals, such as mistaking b for d or reading “was” as “was”. He concluded that dyslexia stems partly from a failure to establish a consistent left–right sense, caused by incomplete cerebral dominance. Gillingham translated these theories into a highly structured reading approach that emphasized phonetic order and systematic instruction.

The Orton–Gillingham approach is direct, explicit, multisensory, structured, sequential, diagnostic, and prescriptive. It is not a single program or method but a flexible framework for teaching reading, spelling, and writing. In the hands of a trained instructor, OG provides powerful, individualized instruction that adapts to each learner’s pace and progress.

In OG-based instruction, students first learn individual letters and sounds, often through multisensory drill cards. They then blend these sounds into consonant–vowel–consonant words (e.g., map, hit, Tim). Instruction expands step by step to include letter blends (st, cl, tr) and more complex combinations (sh, ea, tion). Later stages introduce sentence writing, syllabication, dictionary skills, and advanced spelling rules.

Do Orton–Gillingham results hold up in research?

The research evidence on OG is mixed but informative.

- Ritchey & Goeke (2006) reviewed 12 studies involving students from elementary to college levels. Five studies found OG more effective than control methods for all outcomes, while others showed partial or no differences. The most significant gains were for word attack and comprehension (mean effect sizes = 0.82 and 0.76).

- Stevens et al. (2021) conducted a meta-analysis of OG reading interventions for students with or at risk for word-level reading disabilities. They found no statistically significant improvements in phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, or spelling, though average effect sizes still favored OG. Vocabulary and comprehension gains were similarly modest.

- Solari et al. (2021) summarized: “The evidence in favor of OG programs is limited, either due to a mix of positive and negative effects or, more frequently, because available studies of such programs do not meet quality standards.”

In plain terms, OG helps many students, but the results vary and depend heavily on the quality of implementation, intensity, and learner needs. This suggests that additional components may be needed to make dyslexia intervention more complete.

Hence, Edublox builds upon OG, adding three further pillars—cognitive training, targeted brain development, and solid learning principles—to strengthen what traditional phonics-based instruction alone cannot.

Dyslexia treatment and cognitive training

A second pillar of Edublox’s dyslexia treatment program targets cognitive skills — the often-missing piece of traditional phonics-based approaches.

Research shows that children with dyslexia struggle not only with reading, spelling, and writing but also with multiple underlying cognitive deficits. Studies in cognitive psychology and neuroscience have linked dyslexia to weaknesses in:

“Cognition” refers to the act or process of knowing. Cognitive skills are the mental tools that make learning possible; they determine how we learn rather than what we know.

- Phonological and phonemic awareness

- Verbal fluency

- Attention and executive functioning

- Visual attention and visuospatial abilities

- Processing speed

- Short-term, working, and long-term memory (both auditory and visual)

- Rapid naming

Weaknesses in these skills interfere with a process known as orthographic mapping — the brain’s ability to link a word’s sounds, spelling, and meaning and store them together for instant recognition. Orthographic mapping allows fluent reading and accurate spelling; when it fails, every word feels new each time it is seen.

Unfortunately, cognitive training (popularly known as brain training) has fallen out of favor among many learning-disability practitioners. The BBC science program Bang Goes the Theory conducted a study that greatly contributed to their skepticism. In this study, 11,430 adults performed online cognitive tasks for 10 minutes a day, three times a week, over a six-week period. Although participants improved on the tasks they practiced, there was no evidence of transfer to untrained tasks, even those closely related ones (Owen et al., 2010).

However, the training time was extremely short. Participants completed an average of just 24 sessions — roughly four hours of total practice. To put that into perspective, fitness expert Bobby Maximus (2018) notes that achieving physical fitness requires about 130 hours of exercise. The brain is no different; even ten hours of cognitive work would yield little or no measurable change.

This is why Edublox’s approach integrates systematic, high-repetition cognitive training over sustained periods. The goal is to develop the foundational skills that enable reading instruction to stick and transfer naturally to real-world learning.

Dyslexia treatment targeting two brain regions

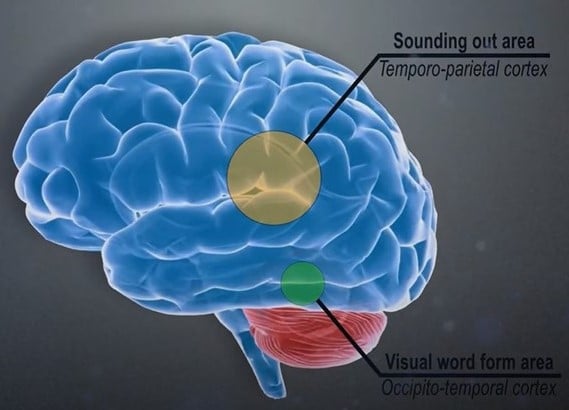

A third pillar of Edublox’s dyslexia treatment program focuses on developing two key brain regions involved in reading — one that helps children sound out words, and another that allows them to recognize whole words instantly.

Research shows that learning to read engages a network of brain regions, but two are especially important:

- The left inferior parietal lobule, responsible for word analysis, grapheme-to-phoneme conversion, and the integration of sound and meaning.

- The left occipitotemporal region, known as the visual word form area (VWFA), often described as the brain’s visual dictionary. This region enables fast, automatic word recognition.

In the most extensive study of its kind, Brem et al. (2020) confirmed that the VWFA is essential for fluent reading. Other research, including Pedago et al. (2010), has found that this area plays a crucial role in discriminating letter orientation, supporting what teachers have long observed: confusion between b and d is one of the classic symptoms of dyslexia.

Given that the strongest under-activation in children with dyslexia occurs in the occipitotemporal cortex, this area should be a primary target for intervention. Yet, many dyslexia treatments have historically overlooked it.

Edublox’s dyslexia treatment program bridges that gap. While the Orton–Gillingham approach excels at strengthening the brain’s “sounding-out” region, Edublox simultaneously targets the VWFA through cognitive and reading exercises, training the brain to recognize words accurately, automatically, and at speed.

Learning principles in dyslexia treatment

The application of educational learning principles is a crucial — yet often overlooked — aspect of dyslexia intervention. Psychologist Edward Thorndike (1874–1949) referred to these as the “laws of learning,” laying the conceptual groundwork for effective learning. Below are examples of Edublox’s learning principles as applied to the treatment of dyslexia. These foundational strategies help children not only learn to read and write, but also retain and apply their skills with confidence.

1) Learning is a stratified process

The idea that learning is layered — or stratified — was already emphasized by educational philosopher Johann Herbart (1776–1841). He argued that we never learn in isolation but always through the lens of prior experience and knowledge. As Mursell (1954, pp. 210–211) explained: “The first consideration in properly organized learning would be to ensure that the learner had the right background.” In other words, previous knowledge can either support or hinder learning. Foundational skills must be mastered before progressing — whether in math, sports, or reading.

2) Cognitive skills training should be multi-cognitive

Just as a well-balanced physical workout is essential to avoid muscular imbalance (think overtrained biceps and the classic “Popeye syndrome”), cognitive training must also be holistic. The brain, like the body, can become lopsided if only one area is targeted.

In a study by Maguire et al. (2006), London taxi drivers who developed enlarged posterior hippocampi (from extensive navigation) showed a corresponding decrease in anterior hippocampal volume. This trade-off suggests that over-developing one cognitive skill might come at the expense of others.

That’s why Edublox’s approach is multi-cognitive — training a range of mental faculties in tandem. Further research supports this mutualistic model of intelligence. For example, better reasoning skills can accelerate vocabulary growth, and a stronger vocabulary can, in turn, boost reasoning ability (Kievit et al., 2017).

3) Cognitive skills can only be improved by task loading

Enhancing cognitive skills requires more than just practice — it involves task loading, or gradually increasing difficulty to push the brain beyond its comfort zone.

In a classic experiment, Ericsson and Chase trained a student (nicknamed SF) to recall increasingly long strings of random digits. After 250 hours of training, SF could repeat over 80 digits — an astonishing feat. However, when asked to recall letters instead of numbers, his performance returned to normal levels. The reason? SF had used mental shortcuts, converting digits into familiar race times (Shenk, 2010). He hadn’t improved his general memory; he’d simply learned a clever trick.

This illustrates the need to design cognitive training that prevents reliance on hacks and shortcuts. At Edublox, we employ a range of exercises to ensure that students truly develop cognitive skills, not just strategies.

4) New knowledge and skills cannot be learned without repetition

Throughout history, repetition — often referred to as drill and practice — has been regarded as a cornerstone of effective teaching. Yet in the 1920s and 1930s, it fell out of favour, with critics equating repetition and rote learning with poor teaching. The assumption was that good teachers avoided drills and focused instead on “higher-order” thinking.

However, when used appropriately, repetition is not low-level — it is foundational. As Brophy (1986) noted, drill-and-practice is just as essential to complex and creative performance as it is to a virtuoso violinist.

Repetition is crucial for students with learning difficulties. A meta-analysis of 85 academic intervention studies found that the most successful outcomes, regardless of method, came from programs that included systematic drill, repetition, practice, and review (Swanson & Sachse-Lee, 2000).

Neuroscience backs this up. Repetition forms the connections (synapses) between brain cells. Without it, key neural pathways fail to develop — and those that are formed but used too infrequently may be pruned away entirely (Hammond, 2015; Bernard, 2010).

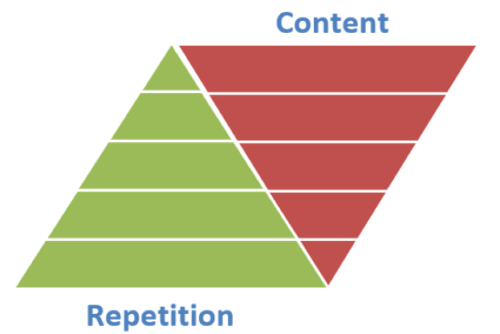

5) A “pyramid of repetition” needs to be constructed for the beginner learner

This principle, derived from the work of Dr. Shinichi Suzuki, emphasizes that beginner learners require extensive repetition when they first start learning a new skill. Still, over time, they require less to master new material.

In Nurtured by Love (1993), Suzuki tells the story of a little parakeet named Peeko. It took 3,000 repetitions of the word “Peeko” over two months before the bird began to say it. After that, the trainer added “Miyazawa,” and after just 200 repetitions, Peeko could say its full name. When the trainer later developed a cough, Peeko even mimicked it too — demonstrating how learning can accelerate once a foundation is established.

Suzuki offers another example from Mrs. Yano, a teacher who trained young children to memorize and recite classic haiku. [A haiku is a short Japanese poem consisting only of three lines.] At first, students needed to hear a poem ten times to remember it. By the second term, they managed after three or four repetitions. By the third term, they needed to hear a haiku only once to recall it.

This is the essence of the “pyramid of repetition”: start with frequent repetition and gradually reduce it as fluency builds. Suzuki (1993, p. 6) explains:

“Once a shoot comes out into the open, it grows faster and faster… talent develops talent and… the planted seed of ability grows with ever-increasing speed.”

The bottom line

By combining cognitive training with systematic reading instruction that targets both the brain’s sounding-out area and the VWFA, while applying fundamental learning principles, the way is paved to improve the reading and writing abilities of children with dyslexia — and help them overcome their challenges.

Watch our playlist of customer reviews and experience how Edublox’s dyslexia treatment program helps overcome signs and symptoms of dyslexia, and book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs. We cater to a variety of dyslexia types.

References for Dyslexia Treatment Program for Children

- Bernard, S. (2010). Neuroplasticity: Learning physically changes the brain. Edutopia.

- Brem, S., Maurer, U., Kronbichler, M., Schurz, M., Richlan, F., Blau, V., & Richardson, U. (2020). Visual word form processing deficits driven by severity of reading impairments in children with developmental dyslexia. Scientific Reports, 10, 18728.

- Brophy, J. (1986). Teacher influences on student achievement. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1069–1077.

- Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Kievit, R. A., Lindenberger, U., Goodyer, I. M., Jones, P. B., Fonagy, P., Bullmore, E. T., & Dolan, R. J. (2017). Mutualistic coupling between vocabulary and reasoning supports cognitive development during late adolescence and early adulthood. Psychological Science, 28(10): 1419-31.

- Knowles, J. (2017). Dyslexia: An exploration of the role of teachers, schools and parents in the identification and support of students with dyslexia in one local authority in England [Doctoral dissertation, London South Bank University]. LSBU Open Research Repository.

- Maguire, E. A., Woollett, K., & Spiers, H. J. (2006). London taxi drivers and bus drivers: A structural MRI and neuropsychological analysis London taxi drivers and bus drivers. Hippocampus, 16(12): 1091-101.

- Maximus, B. (2018, January 3). I’ve helped thousands of people get in shape. Here’s the fastest way to see results. Men’s Health.

- Mursell, J. L. (1954). Successful Teaching: Its Psychological Principles (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw‑Hill Book Company, Inc.

- Novembli, M. S., & Azizah, N. (2019, April). Mobile learning in improving reading ability dyslexia: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Special and Inclusive Education (ICSIE 2018) (pp. 220–226). Atlantis Press.

- Owen, A. M., Hampshire, A., Grahn, J. A., Stenton, R., Dajani, S., Burns, A. S., Howard, R. J., & Ballard, C. G. (2010). Putting brain training to the test. Nature, 465(7299), 775–778.

- Ritchey, K. D., & Goeke, J. L. (2006). Orton-Gillingham and Orton-Gillingham-based reading instruction: A review of the literature. The Journal of Special Education, 40(3), 171–183.

- Shenk, D. (2010). The genius in all of us. Doubleday.

- Solari, E., Petscher, Y., & Hall, C. (2021, March 29). What does science say about Orton–Gillingham interventions? An explanation and commentary on the Stevens et al. (2021) meta-analysis. PsyArXiv.

- Stevens, E. A., Austin, C., Moore, C., Scammacca, N., Boucher, A. N., & Vaughn, S. (2021). Current state of the evidence: Examining the effects of Orton–Gillingham reading interventions for students with or at risk for word-level reading disabilities. Exceptional Children, 87(4), 397–417.

- Swanson, H. L., & Sachse-Lee, C. (2000). A meta-analysis of single-subject design intervention research for students with LD. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(2), 114-36.

- Suzuki, S. (1993). Nurtured by Love (2nd ed.). USA: Summy-Birchard, Inc.

Dyslexia Treatment Program for Children was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), a reading specialist with 30+ years of experience in the learning disabilities field, and medically reviewed by Dr. Zelda Strydom (MBChB).