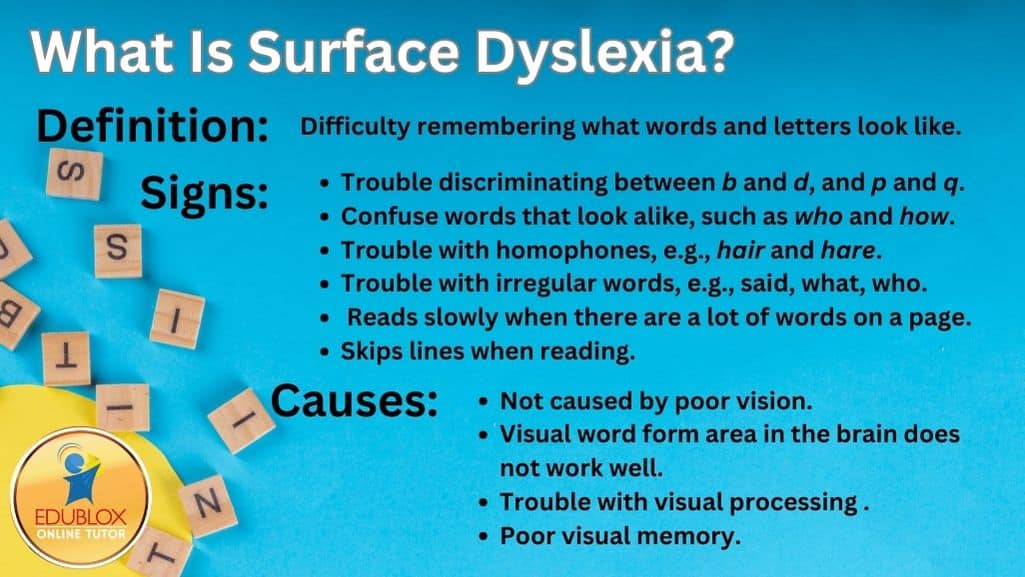

Surface dyslexia is a specific form of dyslexia that refers to individuals who struggle with whole-word recognition and irregularly spelled words. In this article, we discuss what surface dyslexia looks like, how it differs from other dyslexia types, and its causes.

We specialize in helping children overcome the symptoms of surface dyslexia. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

Table of contents:

- What is dyslexia?

- What is surface dyslexia?

- Signs of surface dyslexia

- Causes of surface dyslexia

- Overcoming the symptoms

- Key takeaways

What is dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a type of learning disability that affects how well someone can read and spell.

There are two broad categories of dyslexia: acquired and developmental. Acquired dyslexia occurs when a good reader and speller loses some of their reading or spelling ability due to a brain injury. Developmental dyslexia occurs when children have trouble with reading and spelling from the outset.

In the 1970s, the theory of a dual route model of reading was proposed. This theory suggests two interactive yet distinctive pathways: a route that recognizes high-frequency words automatically and a phonological decoding route that pronounces unfamiliar words. Weakness in either pathway could affect the development of reading skills and result in two different subtypes of dyslexia: phonological dyslexia, i.e., difficulty with nonword reading, and surface dyslexia, i.e., difficulty with irregular word reading (Mather & Wendling, 2012).

What is surface dyslexia?

Some people with dyslexia have trouble making sense of the sounds that make up words. These sounds are called phonemes. A child or adult whose reading difficulty is caused by trouble understanding the different phonemes in words has a weakness in phonological processing and is said to have phonological dyslexia or dysphonetic dyslexia.

For some people, the difficulty is not sound-based but more visual. A child may find it hard to recognize whole words, even if they’ve seen it umpteen times. For a proficient reader, the shapes of words are immediately recognizable, almost like the faces of familiar people. If a child struggles to remember sight words, the problem may stem from an inability to recall these shapes, greatly affecting their fluency.

This type of dyslexia has the name surface dyslexia. Because it relates to how we see words, this type is also known as visual dyslexia. A third name for this is orthographic dyslexia. This term refers to the fact that visual dyslexia often causes problems for spelling, because orthography is another term for spelling. A fourth term that can appear in dyslexia studies is dyseidetic dyslexia. This is just an alternative way to refer to surface, visual, or orthographic dyslexia, depending on the preferences of individual practitioners.

Surface dyslexia vs. other dyslexia types

Research findings indicate a higher incidence rate of phonological dyslexia in the English language than in other languages. English has an opaque orthography, a writing system in which the relationships between letters and sounds are inconsistent, and the language permits many exceptions. Surface dyslexia, on the other hand, has a higher incidence in languages with transparent orthography. Contrary to English, transparent languages show high consistency in grapheme-phoneme correspondences. Therefore, dyslexia affecting phonology is the most common type of dyslexia in English-speaking children.

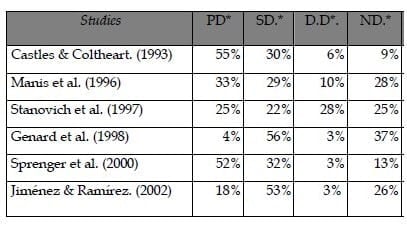

Below are the results of studies of different orthographies, comparing the proportion of students with

> Phonological dyslexia (PD),

> Surface dyslexia (SD),

> Double deficit dyslexia, meaning they have both types (DD), and

> Non-deficit (ND) (Jiménez, 2012):

According to Frith (1985), those who are termed developmental phonological dyslexics are children who have encountered difficulties in entering the alphabetic reading stage. By contrast, children who have been labeled developmental surface dyslexics have found it difficult to make the subsequent transition from the alphabetic stage to the orthographic processing stage and continue to read and spell phonologically.

Stanovich et al. (1997) concluded that genetic factors were more involved in phonological dyslexia, and environmental factors were more involved in surface dyslexia.

Signs of surface dyslexia

Hultquist (2006) lists the following reading patterns and signs as indicators of surface dyslexia:

- Children — or adults — with surface dyslexia may have trouble discriminating between the letters b and d, and p and q.

- They might also confuse words that look alike, such as was and saw, who and how, thought and through, and young and youth.

- They may also confuse lookalike numbers, such as 2 and 5 or 17 and 71.

- They may confuse the order of letters in words. For instance, they might be able to remember all the letters in the word two but be unable to recall if the w or the o comes first. Sometimes, they spell the same word two or more different ways in the same piece of writing because they cannot recall how it is supposed to look.

- Some children have trouble remembering the differences between homophones. Homophones are words that sound the same but are spelled differently and have different meanings. For example, hair and hare are homophones.

- They have trouble with irregular spellings. Irregular words cannot be sounded out because they are not spelled the way they are pronounced. Some of the most common words in English are irregular words, for example, said, what, who, one, does, come, yacht, and colonel.

- Unlike people with phonological dyslexia, they are often good at reading new words as long as those words sound the way they are spelled. They can even sound out words like apparatus or astronomer, although they might get the accent in the wrong place or divide the syllables incorrectly.

- When they spell words, they usually get all the sounds written down but do not use the correct letters. They might spell said as sed, thought as thot, make as mack, or each as ech.

- They often read more slowly and make more errors when there are a lot of words on a page.

- They might also skip lines when they read.

Examples of surface dyslexia

The spelling of children with phonological dyslexia can often not be identified, even by the child, because they do not follow phonetic patterns. A nine-year-old girl with phonological dyslexia wrote a story about a frog and a duck. This sentence was part of her story: “pesel be klait forg and baky.” It says: “please be quiet frog and duck.”

However, children with surface dyslexia spell phonetically but not bizarrely, e.g., hav (have), wer (were), whith (with), onere (owner), villeg (village), spers (spears), prity (pretty), tung (tongue), cretchirs (creatures), grabed (grabbed), bildings (buildings), colect (collect), vacashun (vacation), and arkialijest (archeologist).

Causes of surface dyslexia

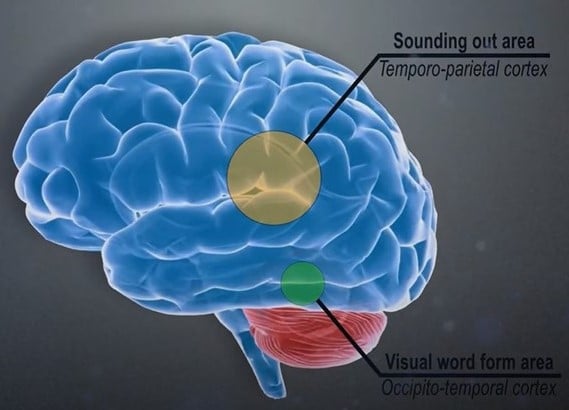

Surface dyslexia is not caused by poor vision and cannot be cured with eyeglasses. The problem is not with the child’s eyes but with how the child’s brain interprets the letters in words. The part of the brain that does not work well in the case of a child with surface dyslexia is most likely the visual word form area (VWFA).

Two separate brain regions are involved in reading: one in sounding out words and the other in seeing words as pictures.

Neuroscientists at Georgetown University Medical Center (2016) concluded that skilled readers can recognize words at lightning-fast speed when they read because the words have been placed in a sort of visual dictionary. This part of the brain is known as the VWFA and functions separately from an area that processes the sounds of written words.

In the most extensive study of its kind, Brem et al. (2020) confirmed that the VWFA is essential to fluent reading. Noteworthy, research by Pedago et al. (2011) shows that the ability to distinguish the orientation of letters, for example, to differentiate between a b and a d, is located in the VWFA.

Furthermore, while phonological processing skills are foundational to learning phonics, visual processing skills (such as spatial relations, form discrimination, and visual memory) are foundational to orthographic processing. Learning irregular words and homophones, for example, requires a good visual memory.

Research findings suggest that visual processing contributes to reading acquisition independently of phonological skills, so a deficit in visual processing may prevent a person from becoming a proficient reader (Dubois et al., 2007).

Developing the VWFA and improving cognitive skills like visual processing and visual memory should, therefore, be the prime targets for intervention. And that, exactly, is what Edublox does.

Overcoming the symptoms

In current practice, different types of dyslexia are treated similarly. Most remedial programs tend to emphasize the utilization of phonics. Phonics-based programs will be of little use to children with orthographic dyslexia as they get drilled on something they already know.

While children do not ‘outgrow’ dyslexia, its symptoms can be overcome with a targeted approach. Below are success stories of children who made significant improvements, overcame their dyslexia symptoms, and the difference it made to their lives:

Key takeaways

Authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), a reading specialist with 30+ years of experience in the learning disabilities field.

.

References and sources:

Brem, S., Maurer, U., Kronbichler, M. et al. (2020). Visual word form processing deficits driven by severity of reading impairments in children with developmental dyslexia. Scientific Reports, 10.

Dubois, M., De Micheaux, P. L., Noël, M. P., & Valdois, S. (2007). Preorthographical constraints on visual word recognition: evidence from a case study of developmental surface dyslexia. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 24(6): 623–660.

Frith, U. (1985). Beneath the surface of developmental dyslexia. In K. Patterson, J. Marshall, & M. Coltheart (Eds.), Surface dyslexia: Neurological and cognitive studies of phonological reading (pp. 301–330). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Georgetown University Medical Center (2016, June 9). In the brain, one area sees familiar words as pictures, another sounds out words. Retrieved July 15, 2019 from https://bit.ly/2XLzNHd

Hultquist, A. M. (2006). An introduction to dyslexia for parents and professionals. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Jimenez, J. E. (2012). The role of phonological processing in dyslexia in the Spanish language. In T. N., Wydell, & L. Fern-Pollak (Eds.), Dyslexia – A comprehensive and international approach (pp. 29‐46). Croatia: InTech.

Mather, N., & Wendling, B. J. (2012). Essentials of dyslexia assessment and intervention. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Pedago, F., Nakamura, K., Cohen, L., & Dehaene, S. (2011). Breaking the symmetry: Mirror discrimination for single letters but not for pictures in the Visual Word Form Area. Neuroimage, 55: 742-749.

Stanovich, K. E., Siegel, L. S., & Gottardo, A. (1997). Converging evidence for phonological and surface subtypes of reading disability. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89: 114-127.