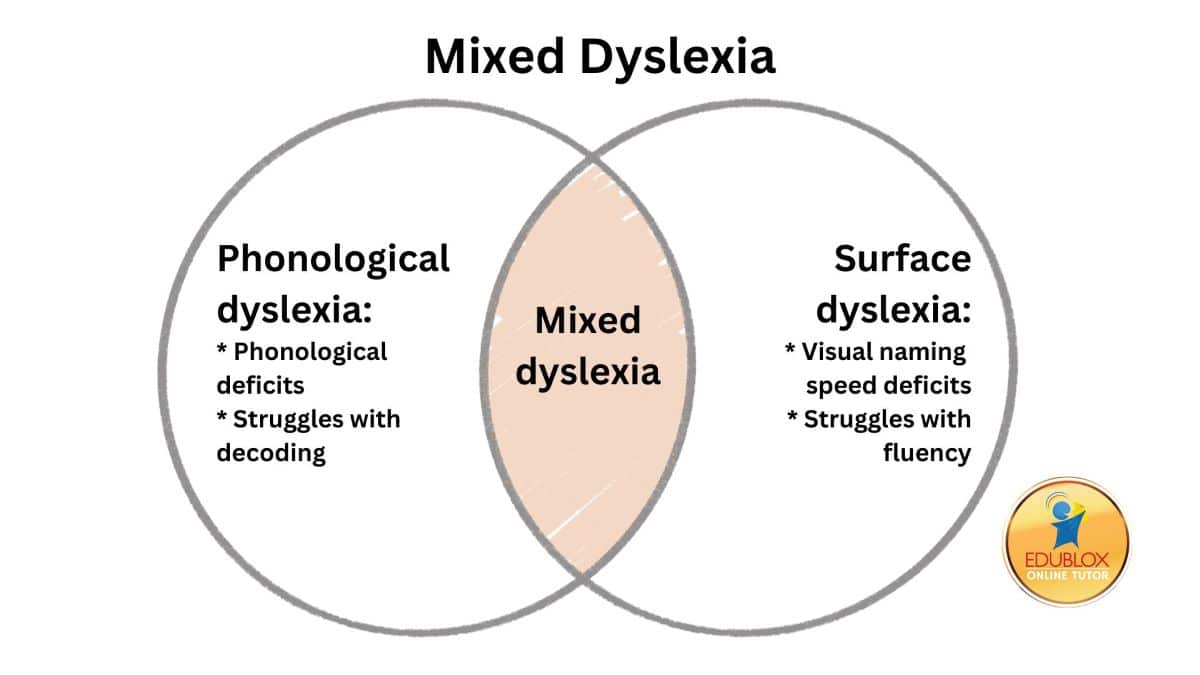

Mixed dyslexia, also known as double-deficit dyslexia, is a severe form of dyslexia caused by deficits in phonological processing and visual naming speed. Due to these deficits, students struggle with both decoding and fluency; most read at the bottom five percentiles on standardized measures.

We specialize in helping children overcome the symptoms of mixed dyslexia. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

Table of contents:

- Overview

- Pointers to mixed dyslexia

- Prevalence of mixed dyslexia

- Causes of mixed dyslexia

- Intervention for mixed dyslexia

Overview

Dyslexia is a learning disability. People with dyslexia have trouble reading at a good pace and without mistakes. They may also have difficulties with reading comprehension, spelling, and writing. Estimates of the affected school-age population around the world vary from 5 to 17 percent, and it is estimated that 80 percent of all individuals diagnosed with some type of learning disability have dyslexia.

As with most disorders, dyslexia can vary in severity, and there are various types. Children with phonological deficits typically have phonological dyslexia, while children with visual naming speed deficits typically have surface dyslexia. Synonyms for phonological dyslexia are auditory dyslexia and dysphonetic dyslexia. Synonyms for surface dyslexia are orthographic dyslexia, visual dyslexia, and dyseidetic dyslexia.

With phonological dyslexia, a person has difficulty associating sounds with letters or groups of letters; with surface dyslexia, a person has difficulty recognizing familiar words. Children with mixed dyslexia have both dyslexia types and, therefore, struggle with decoding and fluency, making reading and spelling extremely challenging. Most of them read at the bottom five percentiles on standardized measures.

Pointers to mixed dyslexia

Children with phonological dyslexia have trouble breaking words into syllables and smaller sound units called phonemes. For example, if one says a word out loud to a child with weak phonemic skills, they can hear it just fine and repeat it back. However, they have trouble telling how to split it into the different sounds that make up this word. Difficulties in this area can make it challenging for readers to match phonemes with their written symbols (graphemes), which makes it hard to sound out or “decode” words.

The most typical indicator of a disabled reader’s impaired phonological-based decoding abilities is a severely reduced ability to decode nonsense words. Nonsense words are made-up words one will not find in an English dictionary. Words like fim or stap. The idea is for the child to apply their grapheme-phoneme correspondence rules in a context-free situation. The word ckad, for example, would not be used as a nonsense word, as ‘ck’ is never found at the start of a word in English.

Children with surface dyslexia, on the other hand, struggle to recognize words by sight. Sight-reading is an essential skill for a couple of reasons. One is that some words have tricky spellings. For example, words like weight and debt can’t be sounded out — readers need to memorize them. The other reason has to do with reading fluency. To read quickly and accurately, kids need to recognize many common words at a glance — without sounding them out (Newcombe & Marshall, chap. 2, 2017).

A typical pointer to surface dyslexia is a deficit in visual naming speed. The best-known measure of visual naming speed is the rapid automatized naming (RAN) test, designed by Denckla (1972) and developed by Denckla and Rudel. This test involves rapidly naming a visual array of 50 stimuli consisting of five symbols in a given category (e.g., letters, numbers, colors, or objects) presented ten times in random order (Wolf & Bowers, 1999).

Rapid letter naming requires attention to the letter stimulus and visual processes such as visual discrimination, pattern identification, integration of pattern identification with stored orthographic and phonological representations, and retrieval from long-term memory (Wolf & Bowers, 1999).

Naming-speed deficits have been demonstrated in impaired readers across several language systems, such as German, Dutch, Finnish, and Spanish. In addition, naming speed plays a vital role in learning to read regardless of whether the sample subjects used an alphabetic or non-alphabetic writing system, such as Chinese or Japanese (Araújo et al., 2015).

Children with mixed dyslexia have both dyslexia types and, therefore, struggle with decoding and fluency, making reading and spelling extremely challenging. Most of them read at the bottom five percentiles on standardized measures.

Prevalence of mixed dyslexia

Lovett and colleagues (2000) conducted a study with 166 children with severe reading disabilities, ages 7 to 13. The researchers aimed to categorize children’s difficulties according to the presence or absence of a phonological and naming-speed deficit.

The data of 84 percent of the sample (140 children) were submitted for further analysis, revealing that 54% of the sample demonstrated a double deficit, 24 percent had a single naming-speed deficit, and 22 percent had a phonological deficit. The children with the double deficit were more severely impaired than children with single deficits.

However, opponents of the mixed dyslexia or double-deficit dyslexia subtype have suggested that naming speed problems do not represent an independent core deficit but rather merely reflect problems in phonological processing; naming visual items is thought to depend on the fast retrieval of phonological codes, which in turn might be influenced by phonological problems in dyslexia (Vaessen et al., 2009).

Causes of mixed dyslexia

Deficits in phonological processing and visual naming speed are not symptoms of dyslexia; instead, they are cognitive deficits that cause dyslexia. In addition to phonological processing and visual naming speed, cognitive psychology has now linked many other cognitive skills to dyslexia, including processing speed, working memory, and visual long-term memory for details.

Norton et al. (2014) found neurofunctional evidence for mixed or double-deficit dyslexia. Through an fMRI study, the authors observed that the double-deficit group showed less activation in the frontoparietal reading network as compared with the single phonological deficit group, who in turn showed less activation than the no deficit group. On the other hand, the double-deficit group showed less cerebellar activation as compared with the single naming speed deficit group, who in turn showed less activation than the no deficit group.

Brain studies have linked especially two brain areas to dyslexia: the left occipitotemporal cortex (shown in yellow) and the left inferior parietal lobe (shown in red). The left occipitotemporal cortex includes the so-called visual word form area (VWFA), thought critical for reading, and is most likely the brain area that does not work well in pure surface dyslexia.

Neuroscientists at Georgetown University Medical Center concluded that skilled readers can recognize words at a lightning-fast speed when they read because the words have been placed in a sort of visual dictionary. This part of the brain, the VWFA, functions separately from an area that processes the sounds of written words (Glezer et al., 2016).

In the most extensive study of its kind up to date, Brem et al. (2020) confirmed that the VWFA is vital to fluent reading and that this brain region should be a prime target for supportive interventions.

The left inferior parietal lobe is said to be involved in word analysis, grapheme-to-phoneme conversion, and general phonological and semantic processing. It is most likely the brain region that does not work well in pure phonological dyslexia.

With mixed dyslexia, both the left occipitotemporal cortex and the left inferior parietal lobe are likely defective.

Imaging also reveals compensatory overactivation in other parts of the reading system (shown in green). The compensatory neural systems allow a dyslexic person to read more accurately. However, the critical visual word-form area remains disrupted, and difficulties with rapid, fluent, automatic reading persist. The person with dyslexia continues to read slowly (Shaywitz, 2005).

Intervention for mixed dyslexia

An important aspect of mixed dyslexia concerns intervention. Since multiple cognitive skills underlie reading, intervention programs that target numerous cognitive skills are a better solution than programs targeting cognitive skills selectively. Edublox’s dyslexia intervention thus aims to develop multiple cognitive skills.

Also, while readers with phonological deficits benefit most from phonological-based interventions, students with naming-speed deficits and mixed dyslexia will not. Edublox’s dyslexia intervention thus targets the left parietal lobe (the brain region involved in phonological processing) as well as the VWFA (the brain region involved in fluency).

Below is a case study of a student with mixed dyslexia, whose reading improved by 54 percentiles according to the STAR Reading Test.

A mixed dyslexia case study

Maddie had mixed dyslexia. She showed many signs and symptoms of both phonological and surface dyslexia. She scored in the 1st percentile for reading—the lowest percentile—meaning that 99 percent of children her age were reading better than her. She scored in the 6th percentile for phonological awareness, in the 16th for phonological memory, and below the 1st for rapid naming.

People who evaluated Maddie were astounded by the severity of her dyslexia. More than one professional had told Maddie’s parents that she would probably never read. However, her mother, refusing to accept this, embarked on a tireless journey to find help for Maddie.

After many avenues had failed, Maddie started a nine-month journey with Edublox. A reassessment by her psychologist saw improvements in phonological awareness (from the 6th to the 39th percentile), phonological memory (from the 16th to the 30th percentile), and rapid naming (from below the 1st to the 8th percentile). According to the STAR Reading Test, her reading improved by 54 percentiles. Watch the video of their journey below.

More dyslexia case studies

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with mixed dyslexia. Our students are in the United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

Authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational and reading specialist with 30+ years of experience in the learning disabilities field.

References:

Araújo, S., Reis, A., Petersson, K. M., & Faísca, L. (2015). Rapid automatized naming and reading performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(3): 868–83.

Brem, S., Maurer, U., Kronbichler, M. et al. (2020). Visual word form processing deficits driven by severity of reading impairments in children with developmental dyslexia. Scientific Reports, 10.

Glezer, L. S., Eden, G, Jiang, X., Luetje, M., Napoliello, E., Kim, J., & Riesenhuber, M. (2016). Uncovering phonological and orthographic selectivity across the reading network using fMRI-RA. Neuroimage, 138: 248-56.

Lovett, M. W., Steinbach, K. A., & Frijters, J. C. (2002). Remediating the core deficits of developmental reading disability: A double-deficit perspective. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 33(4): 334-58.

Newcombe, F., & Marshall, J. C. (2017). Reading and writing by letter sounds. In K. Patterson, J. Marshall, & M. Coltheart (Eds.), Surface dyslexia: Neurological and cognitive studies of phonological reading. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Norton, E. S., Black, J. M., Stanley, L. M., Tanaka, H., Gabrieli, J. D., Sawyer, C., & Hoeft, F. (2014). Functional neuroanatomical evidence for the double-deficit hypothesis of developmental dyslexia. Neuropsychologia, 61: 235-46.

Shaywitz, S. (2005). Overcoming dyslexia. New York: Vintage Books.

Vaessen, A., Gerretsen, P., & Blomert, L. (2009). Naming problems do not reflect a second independent core deficit in dyslexia: Double deficits explored. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 103(2).

Wolf, M., & Bowers, P. G. (1999). The double-deficit hypothesis for the developmental dyslexia. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91: 415-38.