Ask any parents about their baby, and sooner or later, you are likely to hear about motor milestones, such as “Cassandra just learned to crawl,” “Jesse is finally sitting alone,” or “Angela took her first step last week.”

Parents proudly announce such milestones as their children transform themselves from babies unable to lift their heads to toddlers who grab things off the grocery store shelf, chase a cat, and participate actively in the family’s social life. These milestones are examples of gross motor skills, which involve large-muscle activities, such as moving one’s arms and walking.

What are motor milestones?

Motor milestones are defined as the major developmental tasks of a period that depend on movement by the muscles. The timing of the accomplishment of each motor milestone will vary with each child. Motor milestones depend on genetic factors, how the mother and father progressed through their own development, maturation of the central nervous system, skeletal and bone growth, nutrition, environmental space, physical health, stimulation, freedom, and mental health.

There are two forms of motor development within the motor milestones: gross motor development and fine motor development. These two areas of motor development allow an infant to progress from being helpless and completely dependent to being an independently mobile child. In Child Development (2002), the first volume in the Macmillan Psychology Reference Series, author Joan Ziegler Delahunt explains the difference, while John W. Santrock (2011) summarizes important motor milestones from birth to age twelve in his book with the same title:

Gross motor development

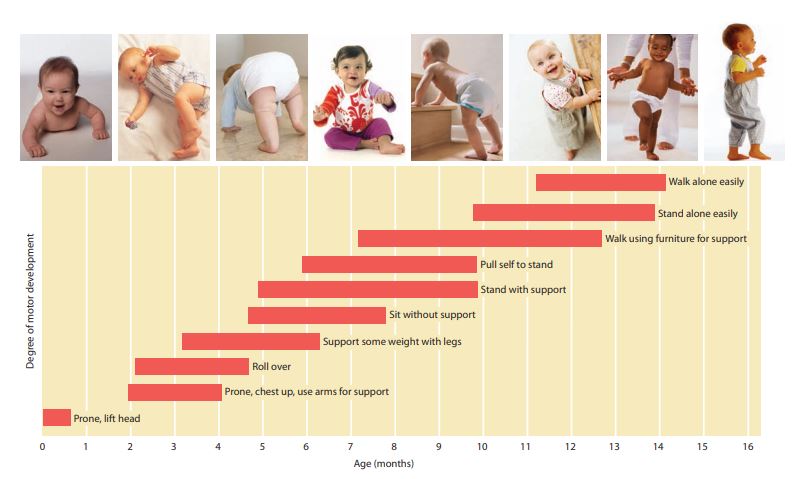

Gross motor development involves skills that require the coordination of the body’s large muscle groups, such as the arms, legs, and trunk. Examples of gross motor skills include sitting, walking, rolling, standing, and more. The infant’s gross motor activity is developed from movements that began while in the womb and from the maturation of reflex behavior. With experience, the infant slowly learns head control, then torso or trunk control, and then rolling, sitting, and eventually walking. The first year of a baby’s life is filled with major motor milestones that are mastered quickly when compared to the motor milestone achievements of the rest of the baby’s development.

.

The motor accomplishments of the first year bring increasing independence, allowing infants to explore their environment more extensively and initiate interaction with others more readily. In the second year of life, toddlers become more motorically skilled and mobile. Motor activity during the second year is vital to the child’s competent development, and few restrictions, except for safety, should be placed on their adventures, says Santrock.

- By 13 to 18 months, toddlers can pull a toy attached to a string and use their hands and legs to climb up several steps.

- By 18 to 24 months, toddlers can walk quickly or run stiffly for a short distance, balance on their feet in a squatting position while playing with objects on the floor, walk backward without losing their balance, stand and kick a ball without falling, stand and throw a ball, and jump in place.

- At 3 years of age, children enjoy simple movements such as hopping, jumping, and running back and forth, just for the sheer delight of performing these activities.

- At 4 years of age, children are still enjoying the same kind of activities, but they have become more adventurous. They scramble over low jungle gyms as they display their athletic prowess. Although they have been able to climb stairs with one foot on each step for some time, they are just beginning to be able to come down the same way.

- At 5 years of age, children are even more adventuresome than they were at 4. It is not unusual for self-assured 5-year-olds to perform hair-raising stunts on practically any climbing object. They run hard and enjoy races with each other and their parents.

- During middle and late childhood, children’s motor development becomes much smoother and more coordinated than in early childhood. For example, only one child in a thousand can hit a tennis ball over the net at the age of 3, yet by the age of 10 or 11, most children can learn to play the sport. Running, climbing, skipping rope, swimming, bicycle riding, and skating are just a few of the many physical skills elementary school children can master.

Fine motor development

In addition to developing gross motor skills, a baby is simultaneously learning fine motor skills. Fine motor development concerns the coordination of the body’s smaller muscles, including the hands and face. Examples of fine motor skills include holding a pencil to write, buttoning a shirt, and turning pages of a book. Fine motor skills use the small muscles of both the hands and the eyes for performance.

- For the first few months, babies spend most of their time using their eyes rather than their hands to explore their environment. The grasping reflex, present at birth, is seen when a finger is pressed into the baby’s palm; the baby’s fingers will automatically curl around the person’s finger. This grasping reflex slowly integrates and allows the development of more mature grasping patterns.

- At four months, babies will begin to reach out for toys with their arms and hands more frequently. The reach looks more like a swipe because the baby is learning to control the arm and hand. Over time, babies learn how to make smoother and more coordinated movements with their arms and hands.

- As children get older, their fine motor skills improve. At 3 years of age, children can pick up the tiniest objects between their thumb and forefinger for some time, but they are still somewhat clumsy at it. Three-year-olds can build surprisingly high block towers, each block placed with intense concentration but often not in a completely straight line. When 3-year-olds play with a form board or a simple puzzle, they are rather rough in placing the pieces. When they try to position a piece in a hole, they often try to force the piece or pat it vigorously.

- By 4 years of age, children’s fine motor coordination is much more precise, and by age 5, children’s fine motor coordination has improved further. Hand, arm, and fingers all move together under the better command of the eye.

- By middle childhood, children can use their hands adroitly as tools. Six-year-olds can hammer, paste, tie shoes, and fasten clothes.

- By 7 years of age, children’s hands have become steadier. At this age, children prefer a pencil to a crayon for printing; printing becomes smaller.

- At 8 to 10 years of age, children can use their hands independently with more ease and precision; children can now write rather than print words. Letter size becomes smaller and more even.

- At 10 to 12 years of age, children begin to show manipulative skills similar to the abilities of adults.

The importance of doing it again and again

The research into brain development in very early childhood has confirmed that babies and toddlers need to be able to move, says Jennie Lindon in her book Understanding Child Development. They need plenty of hands-on learning and safe feet-on and mouth-on contact to learn through their senses. The enjoyable practice of crawling, grasping, and handling objects builds vital neural connections in young brains. Babies and children need to repeat and practice in order to firm up those connections. Neuroscientists express the idea as ‘the cells that fire together wire together.’

This need for happy practice is not restricted to physical development, but so much of early learning is led by the drive to move. Continued experience in any area of development firms up neural connections until they form the complex neural pathways on which babies build more learning. Those connections that are not strengthened by repeated experience are less strong and may fade away.

If all has gone well, a child of 7 or 8 years old is physically coordinated, able to choose from a wide range of large physical movements and fine skills to achieve different purposes. It is an impressive achievement.

Delays in motor milestones

When children are not able to perform the motor skills at the appropriate milestones, their motor development may need to be evaluated by a professional. When motor skills do not progress along a normal trend, a child may be at risk of missing out on potential learning and social experiences.

Children who demonstrate potential motor delays are at risk for continuing these delays throughout later development. For example, a child with weak hand strength and difficulty coordinating finger movement may struggle with handwriting in school.

.

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyslexia, dysgraphia, and other learning disabilities. Our students are in the United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.