Some kids are naturally fast. They run, talk, complete homework assignments, and do all sorts of things at a rate that seems appropriate for their age. Other kids don’t, or perhaps it would be fairer to say they can’t. These are kids who may have what are known as processing speed deficits.

Take the case of John, a 10-year-old boy with ADHD and extremely slow processing speed, who takes three times longer than his 11-year-old sister to complete pretty much any daily task. From the moment John wakes up in the morning, he can’t keep up. It takes him 10 minutes to find his way to the bathroom, even longer to pick out what to wear, and it often takes him so long to figure out what to have for breakfast that he leaves for school without eating anything.

Children with processing problems may start to resent school. It is, therefore, important that parents and teachers alike know the signs and symptoms so that they can intervene.

Table of contents:

- What is processing speed?

- How to recognize processing speed deficits

- Why does processing speed matter?

- How can processing speed be improved?

- Key takeaways

What is processing speed?

Processing speed involves one or more of the following functions: the length of time it takes to perceive and process information and formulate or enact a response. Another way to define processing speed is to say that it is the time required to perform an intellectual task or the amount of work that can be completed within a certain period. Even simpler, one can define processing speed as how long it takes to get stuff done.

There are three main components of processing speed (Burgess, 2016):

- Visual processing: how quickly a student’s eyes perceive information and relay it to the brain (such as reading directions or noticing a teacher’s hand gestures)

- Auditory processing: how quickly a student hears a stimulus and reacts to it (such as following oral instructions or participating in a discussion)

- Motor speed: how strong a student’s fine-motor agility is, leading to academic fluency (such as filling out timed math worksheets).

How to recognize processing speed deficits

Some examples of the types of problems that children with slow processing speed experience include (Braaten & Willoughby, 2014):

- Difficulty processing spoken information fluently or automatically:

- Problems listening to a lecture and taking in all the material presented

- Remembering and following simple directions from a teacher

- Listening and understanding verbal information presented in class by fellow students

- Problems writing information down on paper:

- Writing an assignment in a notebook

- Finishing an exam

- Slower reading fluency skills:

- Having difficulty reading a certain passage in a given period of time during class time or during exams

- Difficulty finishing large reading assignments

- Trouble sustaining attention to a task, not necessarily because the child has attention problems, but because the information is coming at her so quickly that her attention is “lost”

- Difficulty understanding complex directions, particularly those that are given quickly

- Trouble retrieving information quickly from long-term memory. This becomes problematic when a child is called on in class and can’t answer the question quickly enough — even though he knows the answer!

- Problems finishing almost anything (tests, assignments, activities) in an allotted period of time

- Problems with social interactions because the “social scene” moves too quickly to process (includes not just verbal information but nonverbal information that has to be processed quickly).

Why does processing speed matter?

Many studies over many decades have shown that cognitive skills are a determining factor of an individual’s learning ability, according to Oxfordlearning.com, the skills that “separate the good learners from the so-so learners.” In essence, when cognitive skills are strong, learning is fast and easy. Conversely, when cognitive skills are weak, learning becomes a challenge.

Deficits in cognitive skills are said to affect the learning process significantly. Educators and parents should acknowledge this, be on the lookout for abnormal cognitive development, and ensure the successful development of these skills. Processing speed is one of the main components of cognition and is crucial in learning, academic performance, intellectual development, reasoning, and experience.

– Processing speed in daily life

In everyday life, there is a cost to processing everything more slowly, say Braaten and Willoughby in their acclaimed book, Bright Kids Who Can’t Keep Up. Some jobs demand a fast pace. In fact, it would be impossible to perform certain jobs without that quick response rate. Emergency room doctors, jet pilots, and air traffic controllers, among dozens of other careers, place a high priority on the ability to react to information and quickly perform tasks.

Though it might not be obvious, processing speed is also important in school. From being asked to complete “1-minute math worksheets” in second grade to the ability to move between classes in middle and high school (while remembering to get the appropriate books and assignments from a locker in a 4-minute transition period), the ability to do things quickly is highly related to a child’s success in school.

– Processing speed and learning disabilities

Slow processing speed is not a formal learning disability, but it can play a part in learning and attention issues like dyslexia, ADHD, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and auditory processing disorder.

When a student is slow at processing, certain academic tasks can take longer than the average student. In addition, processing speed interacts with other areas of cognitive functioning by negatively impacting the ability to come up with an answer quickly, retrieve information from long-term memory, and remember what one is supposed to be doing at a given time.

Evidence suggests that processing speed problems are a major underlying factor in both dyslexia and ADHD, two disorders that often go hand in hand (Shanahan et al., 2006). Studies also suggest that slow reading and slow motor responses, often seen in those with dyslexia, may be related to slow processing speed (Stoodley & Stein, 2006).

In a sample of 600 families studied by Braaten and Willoughby (2014):

- 70% of the children who had significant processing speed deficits were boys

- language impairments were reported in about 40% of the children with processing speed deficits

- about a third of the parents reported delayed motor development in their children

- 61% of the kids with ADHD also had processing speed weaknesses as compared to their age-matched peers

When these issues go untreated, it can sometimes lead a child to avoid homework or, in extreme cases, avoid school altogether. As a result, these children may appear unmotivated, sluggish, apathetic, and with low energy. Even getting started on tasks is difficult for them.

– Processing speed and executive functioning

Executive function skills allow us to use our intelligence and problem-solving abilities successfully. These skills include abilities such as goal setting, planning, organizing, prioritizing, remembering information in working memory, monitoring our behavior, and shifting back and forth between different tasks or activities. Processing speed is considered an important executive function skill.

Processing speed is more than just another word for executive functions. Here is a good way to think about it: Executive functioning is the car, and processing speed is the engine. Having a faster or more powerful engine means the car can go faster, so good executive function depends on the quality of the engine. More efficient engines allow the car to function at a higher level of efficiency.

– Processing speed and depression

Slow processing speed can take a toll on a child’s academic progress, social relationships, and family dynamics. In addition, the cumulative cost of having had difficulties in these far-reaching domains can result in problems in the emotional realm.

Adolescents with slower processing speed may be at increased later risk of anxiety and depression, according to research done at Edinburgh University. The results add new evidence that lower cognitive ability may be a contributor to depression rather than a consequence of it.

The researchers analyzed data from 705 Scottish participants in a study including follow-up from adolescence into adulthood. At age 16, the participants were evaluated on a simple cognitive processing speed test: reaction time in pressing keys corresponding to numbers (1 to 4) flashed on a screen.

At age 36, the participants completed standard questionnaires assessing depression and anxiety symptoms. In addition, the relationship between reaction time in adolescence and mental health in adulthood was assessed, with adjustment for a wide range of other factors (e.g., education and lifestyle habits).

Slower processing speed at age 16 was associated with increased anxiety and depression symptoms at age 36.

Previous studies have shown that people with more severe depression have slower reaction times and other cognitive deficits. It has generally been assumed that this “psychomotor slowing” is a consequence of depression rather than a risk factor for it. The Edinburgh study suggests that slower processing speed may contribute to the development of mental health disorders, possibly by leading to “increased stress and difficulties responding to adversity earlier in life.”

How can processing speed be improved?

Edublox Online Tutor (EOT) houses several multisensory cognitive training programs that enable students to overcome learning obstacles and reach their full potential.

EOT is founded on pedagogical research and 30+ years of experience demonstrating that weak underlying cognitive skills account for the majority of learning difficulties. Underlying cognitive skills include processing speed.

The key to improving processing speed lies in making stronger connections in the brain, which allow brain signals to travel at higher speeds.

A collaborative study between Edublox, the University of Pretoria (UP), and a primary school in Pretoria CBD has paved the way to show how Edublox Online Tutor can contribute to processing speed development. The study was analyzed as a post hoc research project.

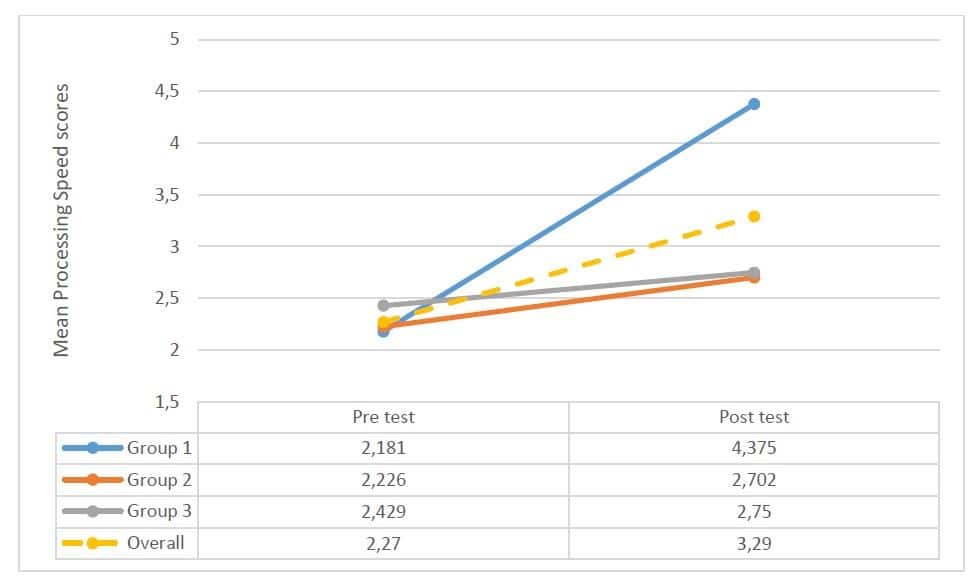

Sixty-four 2nd grade students were divided randomly into three groups: group 1 completed 28 hours of Edublox’s Development Tutor over three weeks; group 2 was exposed to computer games, while group 3 continued with their schoolwork.

Findings suggest that exposure to the Edublox program significantly improved the post-test scores in the processing speed domain. Descriptive statistics showed that while scores improved for all three groups, the children exposed to the Edublox program improved by much more than the other groups. A repeated-measures ANOVA test confirmed the descriptive results and showed significant differences in the improvements in the mean processing speed of the children in group 1 (the Edublox group).

This study follows a trial by educational specialist Dr. Lee DeLorge in Ohio, who put the Edublox program to the test. Sixty-seven students aged 5 to 18 with ADHD, dyslexia, dyscalculia, and non-specific learning disabilities participated in her study. Ninety-four percent of the students improved significantly in processing speed. The results were as follows:

- Thirty-five students with ADHD showed a combined increase of 52.45 percent, from a pre-test average of 37.24 percent to a post-test average of 89.69 percent.

- Thirteen dyslexic students showed a combined increase of 46.76 percent, from a pre-test average of 41.31 percent to a post-test average of 88.07 percent.

- Two students were diagnosed with dyscalculia and showed a combined increase of 57.38 percent, from a pre-test average of 39.76 percent to a post-test average of 97.14 percent.

- The remaining learners were non-specific learning-disabled and showed a combined increase of 64.14 percent, from a pre-test average of 30.40 percent to a post-test average of 94.54 percent.

Interview

In an interview broadcast on WKYC, a television station in Cleveland, Ohio, Dr. DeLorge explained cognitive skills and how Edublox methodology strengthens a child’s cognitive skills.

.

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and other learning disabilities. Our students are in the United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

Key takeaways

.

Bibliography:

Braaten, E., & Willoughby, B. (2014). Bright Kids Who Can’t Keep Up. Help Your Child Overcome Slow Processing Speed and Succeed in a Fast-Paced World. Guilford Press: New York.

Burgess, K. (2016). Understanding and addressing processing speed deficits in the classroom. LDOnline.org

Lee, Cynthia Wei-Sheng PhD; Liao, Chun-Hui MD; Lin, Cheng-Li MSc; Liang, Ji-An MD; Sung, Fung-Chang PhD; & Kao, Chia-Hung MD (2015). Depression and risk of venous thromboembolism: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Psychosomatic Medicine.

Shanahan, M. A., Pennington, B. F., Yerys, B. E., Scott, A., Boada, R., Willcutt, E. G., Olson, R. K., & DeFries, J. C. (2006). Processing speed deficits in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and reading disability. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 584-601.

Stoodley, C. J., & Stein, J. F. (2006). A processing speed deficit in dyslexic adults? Evidence from a peg-moving task. Neuroscience Letters, 399, 264-267.