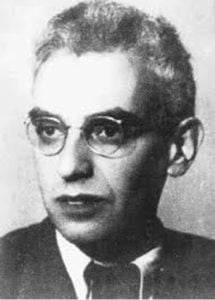

One of the most analyzed memories belonged to a Russian Solomon Shereshevsky, otherwise known as S. He aspired to be a violinist, became a journalist, then a professional mnemonist, and ended his career as a taxi driver in Moscow. According to the famous neuropsychologist Professor Luria, who studied S for thirty years, his memory had no distinct limits.

As a journalist, S never took notes during his interviews, but his articles were detailed and accurate. He told his editor he didn’t need to take notes because he never forgot anything. His editor sent him to Aleksander Luria at a local university for testing.

Luria presented S with 70-digit matrices, complex scientific formulae, and even poems in foreign languages, all of which he could memorize in minutes. He could also report extensive lists of numbers or letters in reverse order. Not only this, but he remembered them years afterward, as well as the clothes Luria had worn on the day he had first learned them!

Even events from early childhood could be recalled, including things that happened when he was still in his crib. There also appeared to be no limit to his digit span, as opposed to the seven to nine items most humans can manage.

Born with synaesthesia

S’s experience of the world around him was quite different from ours. He was born with a condition known as synaesthesia. Synaesthesia is a joining together of sensations that are normally experienced separately. Some synesthetes experience colors when they hear or read words, while others may experience tastes, smells, shapes, or touches in almost any combination. The sensations are automatic and cannot be turned on or off.

In S’s case, he automatically translated the world around him into vivid mental images that lasted for years. He couldn’t help but have a good memory, writes Dominic O’Brien in his book How to Develop a Perfect Memory:

‘If he was asked to memorize a word, he would not only hear it, but he would also see a color. On some occasions, he would also experience a taste in his mouth and a feeling on his skin. Later on, when he was asked to repeat the word, he has a number of triggers to remind him.’

He also used images to remember numbers:

Synesthesia created problems in other areas of his life. The sound of a word would often generate an image quite different from the word’s meaning:

S had a phenomenal imagination, writes Dominic O’Brien:

‘Luria believed that he spent a large part of his life living in the world of his images. As a child, he would visualize the hand on his clock saying 7:30 so he could stay in bed. He could increase his pulse from 70 beats per minute to 100, simply by imagining he was running for a train. In one experiment, he raised the temperature of his left hand and lowered the temperature of the other (both by two degrees) just imagining he had his one hand on the stove while the other was holding a block of ice. He could even get his pupils to contract by imagining bright light!’

The gift was a serious handicap

Unfortunately, S’s gift was a serious handicap. He was unable to block unwanted memories. Also, he had a terrible memory for faces because he memorized them so exactly. People’s faces change with time, lighting, mood, and expression. S had difficulty recognizing faces because they looked so different to him from the ones he had completely memorized in the past.

S had trouble understanding abstract concepts or figurative language. If he couldn’t visualize something, he was stumped. His wife had to explain what ‘nothing’ meant. Luria wrote about him:

S gave up his journalism career and became a professional mnemonist, giving regular shows to paying audiences. Despite his success, he never had great satisfaction as a performer and gave it up after a while. He then became a taxi driver in Moscow, but his life faded into obscurity afterward. Aside from a possible death date in 1958, there seems to be little else available.

.

.

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and other learning disabilities. Our students are in the United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

.