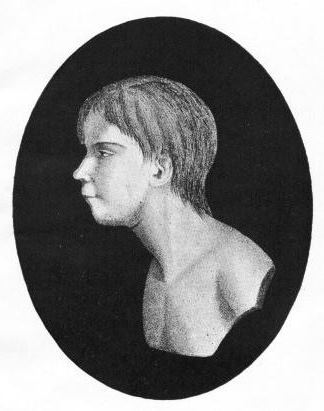

In the late eighteenth century, a child of eleven or twelve was captured, who some years before had been seen completely naked in the Caune Woods in France, seeking acorns and roots to eat. The boy was given the name Victor and is often referred to as the Wild Boy of Aveyron.

In the late eighteenth century, a child of eleven or twelve was captured, who some years before had been seen completely naked in the Caune Woods in France, seeking acorns and roots to eat. The boy was given the name Victor and is often referred to as the Wild Boy of Aveyron.

Victor brought to Paris

When hearing of the capture, a minister of state with scientific interests, believing that this event would throw some light on the science of the mind, ordered that the child be brought to Paris.

In Paris, the boy became nine days of wonder. People of all classes thronged to see him, especially since it was an opportunity to see the romantic theories of the famous Jean-Jacques Rousseau in practice.

Nature versus nurture

Rousseau, a passionate critic of the society of his time, saw the possibility of reforming society through the education of children. In his Émile, he posits a natural development of the child, which must be protected from the influences of society so that the child can grow up as Nature intended him to be.

In essence, Rousseau believed that there is a natural development on which we can rely and which will inevitably take place, provided we can keep in check the “unnatural” influences of society. So, with Victor, the people of Paris had the opportunity to see a child who had grown up according to Rousseau’s ideals.

Rousseau’s theory in practice

What they did see was a degraded human being, human only in shape; a dirty, scarred, inarticulate creature who trotted and grunted like the beasts of the fields, and ate with apparent pleasure the most filthy refuse. Victor was apparently incapable of attending to even elementary perceptions such as heat or cold. He spent his time apathetically rocking himself backward and forward like the animals at the zoo. A “man-animal,” whose only concern was to eat, sleep, and escape the unwelcome attentions of sightseers.

As usual, expert opinion was somewhat derisive of popular attitudes and expectations. The great French educator and psychologist Philippe Pinel examined the boy, declaring that his wildness was a fake and that he was an incurable idiot. He failed to explain how a mentally defective person could have been able to fend for himself in the wilds for any length of time.

Victor and Itard

Victor was assigned to Dr. Itard, who describes the boy’s behavior and his own efforts to teach him to do the things ordinary human beings do, including speaking and reading.

Victor’s tutor tells us that his senses were extraordinarily apathetic. His nostrils were filled with snuff without making him sneeze. He picked up potatoes from boiling water. A pistol fired near him provoked hardly any response, though the sounds of cracking a walnut caused him to turn around.

Itard tried to teach Victor to speak and read. At the end of five years, Victor could identify some written words and phrases referring to objects and actions, and even some words referring to simple relationships such as big and small, and he could use word cards to indicate some of his desires. However, he did not learn to speak.

More stories of feral children

There are many other stories of feral children in the literature, among others, the story of a boy who lived in Syria, who ate grass and could leap like an antelope, as well as of a girl who lived in the forests in Indonesia for six years after she had fallen into the river. She walked like an ape, and her teeth were as sharp as a razor.

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and other learning disabilities. Our students are in the United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

.